German version here.

Everybody, or at least everybody in politics or economics, is talking about a carbon tax at the moment. 61 countries, among them pioneers like Sweden or Switzerland, have it already. But how is it going to affect our food? Are you also wondering, what consequences such a tax would have for our daily grocery shopping in the supermarket, the local farmer’s store or the vegan organic deli? Will ananas be gone and meat unaffordable?

In this post, I will explain to you what science has to say in this regard and later I will also provide you with some cool sample calculations, so make sure to read all of it!

To solve the climate crisis, CO2 Emissions need to be reduced drastically. One way to achieve this is a carbon tax. There are countless proposals for different types of carbon taxes, but the main point is the following: In the production process of nearly all goods, be it apples, shirts or cars, CO2 is emitted, which causes and speeds up climate change. To provide companies with an incentive to save as much CO2 in their production process and to help consumers to opt for products that are low in CO2 emissions, there is this idea to have firms calculate the CO2 footprint of their products and pay taxes for it = carbon taxes.

This was only a very rough overview, because Youtube already offers a bunch of great explanatory videos, for instance this one from the Financial Times or this Ted Talk by Johan Eyckmans.

But coming back to the Schnitzel:

To answer the question, how a carbon tax could affect our food, I have dug through a large number of high-quality scientific studies and official sources, and what I have found out I will tell you in a moment.

But first a little disclaimer: The following studies have all dealt with different types of CO2 taxes. The effects are also different depending on the actual design of the tax, the social and structural characteristics of the local economy, agricultural sector and food supply chain. I guess it makes sense that two carbon taxes of different sizes, one in India and the other in Switzerland, won’t have the same effects, right?

The reason I am saying this is that because of that, the results of country-specific studies can never be directly applied to another country. This means “just because it works in Switzerland, it does not mean that it has to work in Austria”. Nonetheless, one can gain a lot of insights and general tendencies. So, let’s go!

1. Effects of a Carbon Tax on Food

I have compared the current proposals for carbon taxes for Austria, Germany and many other countries:

As of today, food production would be exempted in nearly all proposals for a carbon tax. Yet, there are a number of proposals, how the food sector could still be included (just think of the fiercely debated meat tax, about which I have a video in the pipeline as well, so stay tuned!). In the following I will present you some scientific analyses of current proposals:

This french study from 2019 dealt with the following three options of a CO2 tax:

- A tax on foods high in animal proteins, with a redistribution of the revenue in form of a subsidy of plant protein

- The same tax without the subsidy

- A carbon tax on all foods

The first one calculated a CO2 reduction between 1% and 1.8%, the second scenario interestingly yielded higher reductions between 2,2% and 5,5%. So those two options which only tax foods high in animal proteins predicted no mind blowing effects. Yet in the third case, so in the one where the carbon tax is applied on all foods, a CO2 reduction between 6% and 15% was calculated.

Similar CO2 reduction potential was found for carbon taxes on all foodstuffs, so scenario three of the aforementioned study was predicted to lie between 6% and 10%, by this study for the UK, this study for Spain and this one for Denmark.

Now coming to the question of how much more money one would have to spend on food in case of a carbon tax: The first scenario, per definition, leads to a situation, where, on average, people spend the same amount of money on food. This is because the state would use the money which it raises with the tax on animal protein to subsidize plant protein. So a person who consumes both in equal proportions would not spend more nor less in the supermarket than before, because meat, milk and eggs would be more expensive while beans, peas and lentils would be cheaper. What this would mean my individual expenses depends on my buying habits: A vegan person would spend much less on food than without the tax.

The third scenario, so a carbon tax on all foodstuffs (so a not-revenue-neutral one) would lead to an increase in food expenditure between 5% and 11%, but again, this would depend on what each person typically buys and eats.

So back to the Schnitzel. Will it be more expensive, when Austria gets its carbon tax? This clearly depends on how it is designed. In all three scenarios of the aforementioned French study, it would get more expensive. If food is exempted from a carbon tax, the price might stay as it is, or only be affected by higher transport costs.

For the french study one has to note that it only deals with food consumption at home. To take into account consumption in restaurants apparently would have made it too complex.

2. Social Consequences:

The authors of the previously mentioned study from Spain 2015 highlight that exempting fruits & vegetables from the carbon tax would lead to less additional tax burden for people with low incomes. Furthermore, they emphasize that a carbon tax, if it would include the food sector, would incentivize people with low incomes to switch from cheap meat (which would not be so cheap anymore due to the tax) to fruits & vegetables (which would be much cheaper with the tax).

This already shows how important it is to consider the incentives a carbon tax can have on sustainability, social groups and of course people’s nutritional behavior. This should be estimated and taken into account already when the carbon tax is designed, so BEFORE it gets effective. After all, we don’t want poor people to end up eating crisps (which might be vegan and regional) because they can’t afford anything else. Thinking about social consequences is very important for another reason: Currently, in most rich western countries, meat consumption is actually HIGHER for people from lower income classes and LOWER for people in high income classes.

And one further factor plays an important role and should actually feature in any discussion on carbon taxes, but it doesn’t: supply & demand!

There is a mechanism, through which supply & demand influence the effect of a carbon tax. I wanted to explain it to you at this point, but that made the video WAY too long, so I decided I will do a separate one on this topic, which I will link on the screen once it’s out. So make sure to subscribe to my channel so you won’t miss out on it!

I know, this part on supply & demand sounds so technical, but just remember: Whether our Schnitzel gets more expensive depends on supply & demand, and it does NOT depend on the specific legal text telling us who has to pay.

Moreover, market competition plays a role. The more competition on a market (like, for example, is the case for staple foods), the more probable it is that the carbon tax will be transmitted to the consumer. But also this mechanism will be covered in the additional video!

What you need to remember is simply the following: While economists and scientists can calculate how much our Schnitzel IS EXPECTED to increase in price, at the end of the day, the restaurant owner decides the prices on the menu. And this is why no one is able to predict with 100% accuracy how a carbon tax will influence prices.

I know, this is the “it depends” answer science always gives. But I just want to be honest with you and make clear that any prediction on the effects of the carbon tax will always stay exactly that: a prediction. In real life, supply, demand and competition influence the price.

(Example: Source for France).

Just think about that vegan, climate-saving daughter of a lawyer and the truck driver who has four kids to feed. Who will be hit harder if sausages & butter get more pricey? (#bobo)

3. Supply & Demand, Competition

And one further factor plays an important role and should actually feature in any discussion on carbon taxes, but it doesn’t: supply & demand!

There is a mechanism, through which supply & demand influence the effect of a carbon tax. I wanted to explain it to you at this point, but that made the video WAY too long, so I decided I will do a separate one on this topic, which I will link on the screen once it’s out. So make sure to subscribe to my channel so you won’t miss out on it!

I know, this part on supply & demand sounds so technical, but just remember: Whether our Schnitzel gets more expensive depends on supply & demand, and it does NOT depend on the specific legal text telling us who has to pay.

Moreover, market competition plays a role. The more competition on a market (like, for example, is the case for staple foods), the more probable it is that the carbon tax will be transmitted to the consumer. But also this mechanism will be covered in the additional video!

What you need to remember is simply the following: While economists and scientists can calculate how much our Schnitzel IS EXPECTED to increase in price, at the end of the day, the restaurant owner decides the prices on the menu. And this is why no one is able to predict with 100% accuracy how a carbon tax will influence prices.

I know, this is the “it depends” answer science always gives. But I just want to be honest with you and make clear that any prediction on the effects of the carbon tax will always stay exactly that: a prediction. In real life, supply, demand and competition influence the price.

4. Examples

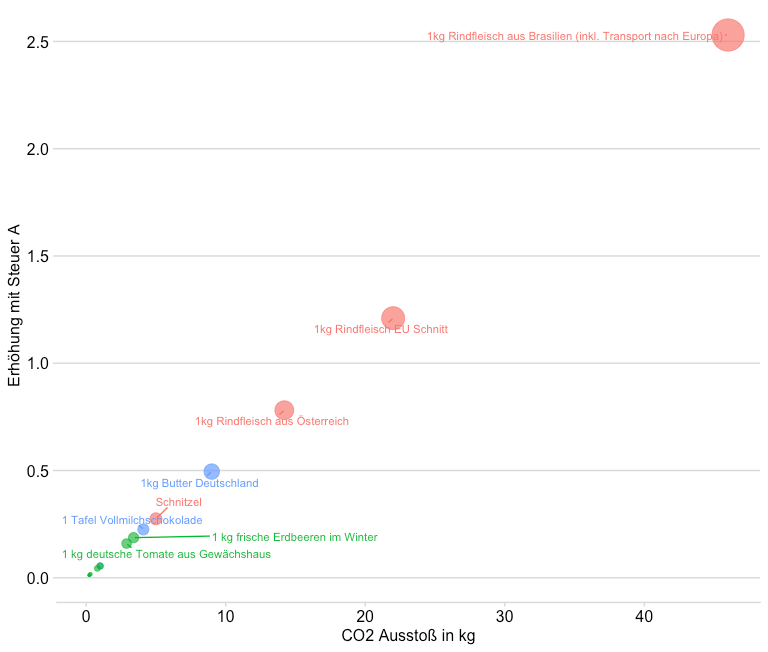

So now that we’ve got that out of our way, I can still show you how a carbon tax of 55€/tonne would affect prices of some Austrian foodstuffs:

I have used the carbon price of 55€/t for this example, because A) Germany has already fixed this one for 2025, and B) it is about the average of what those countries that do already have CO2 taxes. If I’d use a higher price, of course, the price increases would be higher as well.

Let’s start with regular milk: According to this study of the Joint Research Centre from 2019, the emissions per kilo cow’s milk are 1 kg of CO2 equivalent for Austria and Ireland. This is the lowest of the whole EU, which has an average of 1.4 kg. Here it is important to look at the numbers for the country YOU are living in. This article from the website vegan.at for example credits cow’s milk for Austria with 3.2 kg, and thus with more than three times of what soy milk has. Unfortunately I could not easily find out where they got these 3.2 kilos from.

In the following table you can find some more interesting calculations, the sources can be found here.

| Product | CO2 emissions in kg | Price increase (tax 55€/t) |

|---|---|---|

| 1kg beef (Brazil, incl. transport to Europe) | 46 | 2,53€ |

| 1kg beef EU average | 22 | 1,21€ |

| 1kg beef (Austria) | 14,2 | 0,78€ |

| 1kg butter (Germany) | 9 | 0,50€ |

| 1 Schnitzel | 5 | 0,28€ |

| 1 bar milk chocolate | 4,1 | 0,23€ |

| 1 kg fresh strawberries (seasonal & regional) | 3,4 | 0,19€ |

| 1 kg tomato (greenhouse in Germany) | 2,9 | 0,16€ |

| 1L cow’s milk (Austria) | 1 | 0,06€ |

| driving 4,5 km to the supermarket & back | 1 | 0,06€ |

| 1 kg organic avocado (Peru) | 0,8 | 0,04€ |

| 1 kg fresh strawberries (seasonal & regional) | 0,3 | 0,02€ |

| Veggie Spaghetti Bolognese | 0,24 | 0,01€ |

| 1 kg apples (organic, Germany) | 0,2 | 0,01€ |

I just want to point out a few especially interesting ones: For instance, 1 kilo of brazilian beef bought in a store in Austria produces 46 kilos of CO2 equivalents, while on EU average, a kilo of beef produces 22 kilos of CO2 equivalents. And Austrian beef bought in Austria was found to have the world’s lowest CO2 impact beef can have, which is 14,2 kilo (on average). Bear in mind that this is still a lot compared to other foodstuffs.

The rest of the numbers I had to take from German calculations (IFUE 2020), because I could not find them for Austria after spending hours in research. Nonetheless, the agricultural structure of these two countries is highly similar, and imported products like avocados have about the same carbon footprint in Austria and Germany.

And who uses the car to drive to the supermarket has to take that into account as well: A 4.5 kilometers drive in one direction & back again would necessitate 6 cents. Per kilometer, one can count for 110g CO2, a number which is much higher for older cars. (Source: Statista.at).

I have also designed an interactive version of the following plot here (it’s much cooler 🙂

All these small amounts might not sound too high, but long-term they can have a huge impact on people’s consumption decisions, which is actually the goal of a carbon tax: The less CO2 firms use in their production of a good, the cheaper they can sell them. This way, incentives are created for farmers and the food industry to produce ever less CO2-intensive. And for consumers it will be “easier” to buy the environmentally friendly alternatives in the supermarket. Austrian beef would clearly beat its South American competitor, and regional and seasonal fruits & vegetables would be much better off compared to frozen strawberries from New Zealand.

So what about the price of the Schnitzel?

To answer the original question of this video, I used this cool tool from IUFE Germany to calculate how many kilograms CO2 a (German) Schnitzel with potatoes on the side would omit: It’s about 5 kg! And a carbon tax of 55€/t would increase its price by 28 cents. And french fries would drive this price even further up.

With a carbon tax of 100€/tonne CO2, this would already lead to an increase of 50 cents.

Compare this with a vegetarian Spaghetti dish: With its 0.24 kg carbon footprint, its price would increase by only 1 cent.

BUT REMEMBER: Depending on which carbon tax you look at, food could also be exempted. Yet, through the more expensive fuel for production and transport, a carbon tax could still influence food prices. I will look at this more closely in my next video on the question of “Carbon tax: How is a farmer going to fuel his tractor?”

So now it’s up to you! What do you think about the carbon tax? Do you think it would change your consumption patterns and buying decisions?

Or do you have further questions on sustainability and the economy? Let me know in the comments below – I am so curious to hear from you!

And if you want to know more reliable information and well-researched facts about sustainability issues, then first of all click the subscribe button, and then the little bell to receive notifications and not miss any future video. And of course, I would be over the moon if you found this video interesting and helpful and would show it with a thumbs up!

So, stay curious, and we will see each other soon in the next video of LydiaExplains!

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this article are my own. They are uninfluenced, independent and I am not being paid for it. I have researched all sources and facts to my best knowledge and according to the principles of honest, qualitative scientific practice. Nonetheless, I am providing no warranty for them. I included a collection of sources I consider to be key, but I am not claiming them to be complete. You should always check sources and be sceptical when one is talking about “scientific arguments”. Therefore I invite you to check all my sources and form your own opinion.

The following is my video for this article (as of now only available in German).